Wool

Background

As with many discoveries of early man, anthropologists believe the use of wool came out of the challenge to survive. In seeking means of protection and warmth, humans in the Neolithic Age wore animal pelts as clothing. Finding the pelts not only warm and comfortable but also durable, they soon began to develop the basic processes and primitive tools for making wool. By 4000 B.C. , Babylonians were wearing clothing of crudely woven fabric.

People soon began to develop and maintain herds of wool-bearing animals. The wool of sheep was soon recognized as one of the most practical to use. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, wool trade prospered. The English had become proficient in the raising of sheep, while the Flemish had developed the skills for processing. As a result, the British began to sell their wool to the Flemish, who processed the raw material and then sold it back to the English.

The ambitious British soon realized the advantages of both producing and processing their own wool. As Britain began to prosper, it sought to enhance its position by enacting laws and embargoes that would stimulate its domestic production. Some laws, for example, required that judges, professors, and students wear robes made of English wool. Another law required that the dead be buried in native wool. When the American colonies began to compete with the motherland, the English passed a series of laws in an attempt to protect their "golden fleece." One law even threatened the amputation of the hand of any colonist caught trying to improve the blood line of American sheep.

Today, wool is a global industry, with Australia, Argentina, the United States, and New Zealand serving as the major suppliers of raw wool. While the United States is the largest consumer of wool fabric, Australia is the leading supplier. Australian wool accounts for approximately one-fourth of the world's production.

What for centuries was a small home-based craft has grown into a major industry. The annual global output is now estimated at 5.5 billion pounds. Though cotton is the number one plant used for fabrics and the number one fiber overall, the number one source for animal fiber is still wool.

Raw Materials

While most people picture only sheep when they think of wool, other animals also produce fine protein fiber. Various camels, goats, and rabbits produce hair that is also classified as wool.

In scientific terms, wool is considered to be a protein called keratin. Its length usually ranges from 1.5 to 15 inches (3.8 to 38 centimeters) depending on the breed of sheep. Each piece is made up of three essential components: the cuticle, the cortex, and the medulla.

The cuticle is the outer layer. It is a protective layer of scales arranged like shingles or fish scales. When two fibers come in contact with each other, these scales tend to cling and stick to each other. It's this physical clinging and sticking that allows wool fibers to be spun into thread so easily.

The cortex is the inner structure made up of millions of cigar-shaped cortical cells. In natural-colored wool, these cells contain melanin. The arrangement of these cells is also responsible for the natural crimp unique to wool fiber.

Rarely found in fine wools, the medulla comprises a series of cells (similar to honeycombs) that provide air spaces, giving wool its thermal insulation value. Wool, like residential insulation, is effective in reducing heat transfer.

Wool fiber is hydrophilic—it has a strong affinity for water—and therefore is easily dyed. While it is a good insulator, it scorches and discolors under high temperatures. Each fiber is elastic to an extent, allowing it to be stretched 25 to 30 percent before breaking. Wool does, however, have a tendency to shrink when wet.

Design

While some of the characteristics of wool can be altered through genetic engineering of sheep, most of the modifications of design are implemented during the manufacturing of the fabric. Wool can be blended with any number of natural or synthetic fibers, and various finishes and treatments can also be applied.

Different types of fleece are used in producing wool. Lambs' wool is fleece that is taken from young sheep before the age of eight months. Because the fiber has not been cut, it has a natural, tapered end that gives it a softer feel. Pulled wool is taken from animals originally slaughtered for meat and is pulled from the pelt using various chemicals. The fibers of pulled wool are of low quality and produce a low-grade cloth. Virgin wool is wool that has never been processed in any manner before it goes into the manufacturing phase. This term is often misunderstood to mean higher quality, which is not necessarily the case.

These wools and others can be used in the production of two categories of woolen fabrics: woolens and worsteds. Woolens are made up of short, curly fibers that tend to be uneven and weak. They are loosely woven in plain or indistinct patterns. Usually woolens have a low thread count and are not as durable as worsteds. They do, however, make soft, fuzzy, and thick fabrics that are generally warmer than their counterparts.

The mechanization of the woolen cloth industry provides a heady example of the extent of nineteenth-century industrial change. Every step of the process, except shearing the sheep and sorting the wool into different grades, was mechanized between 1790 and 1890. Only the organic aspects of shearing live animals and the value judgments required of human sorters resisted mechanical replication until the twentieth century.

Growth of the American woolen trade was based on more than mechanical change, however. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, American sheep provided wool that was quite satisfactory for "homespun," the rough, durable cloth woven by hand on looms owned by professional weavers who set up shop or moved from town to town with their looms. But domestic cloth was overshadowed in quality by imported material.

Several varieties of sheep bred in England and Europe produced wool vastly superior in quality to American-produced wool. The importation of breeds such as the English Southdowns and Spanish Merinos improved domestic quality and allowed the American woolen industry to compete with the best imports.

The Merino sheep, in particular, with their deeply wrinkled folds producing large quantities of wool, caused a stir among American farmers in the early part of the century. A few "gentlemen farmers" avoided Spanish export restrictions and imported some Merinos. As wool prices rose during the embargo of 1807, a "Merino craze" occurred that pushed the price of fine wool and purebred animals to record levels. Then, in 1810, an American diplomat arranged the importation of 20,000 purebred Merinos, and the woolen industry from Vermont to Pennsylvania to Ohio was changed forever.

William S. Pretzer

Worsted fabrics are made of long, straight fibers with considerable tensile strength. They are usually woven in twill patterns and have a high thread count. The finish tends to be hard, rough, and flat. Also, the insulation

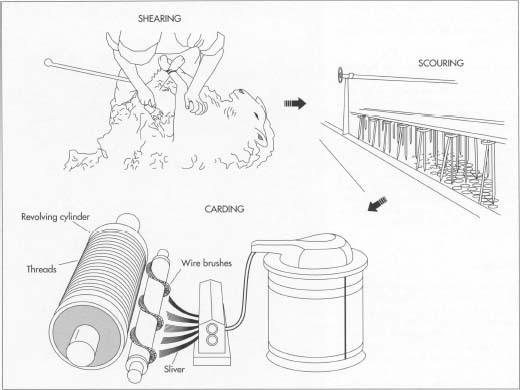

Next, the fleece is carded—passed through a series of metal teeth that straighten and blend the threads into slivers. Carding also removes residual dirt and other matter left in the fibers.

The Manufacturing

Process

The major steps necessary to process wool from the sheep to the fabric are: shearing, cleaning and scouring, grading and sorting, carding, spinning, weaving, and finishing.

Shearing

- 1 Sheep are sheared once a year—usually in the springtime. A veteran shearer can shear up to two hundred sheep per day. The fleece recovered from a sheep can weigh between 6 and 18 pounds (2.7 and 8.1 kilograms); as much as possible, the fleece is kept in one piece. While most sheep are still sheared by hand, new technologies have been developed that use computers and sensitive, robot-controlled arms to do the clipping.

Grading and sorting

- 2 Grading is the breaking up of the fleece based on overall quality. In sorting, the wool is broken up into sections of different quality fibers, from different parts of the body. The best quality of wool comes from the shoulders and sides of the sheep and is used for clothing; the lesser quality comes from the lower legs and is used to make rugs. In wool grading, high quality does not always mean high durability.

Cleaning and scouring

-

3 Wool taken directly from the sheep is called "raw" or

"grease wool." It contains sand, dirt, grease, and dried

sweat (called

suint);

the weight of contaminants accounts for about 30 to 70 percent of the

fleece's total weight. To remove these contaminants, the wool is scoured in a series of alkaline baths containing water, soap, and soda ash or a similar alkali. The byproducts from this process (such as lanolin) are saved and used in a variety of household products. Rollers in the scouring machines squeeze excess water from the fleece, but the fleece is not allowed to dry completely. Following this process, the wool is often treated with oil to give it increased manageability.

After being carded, the wool fibers are spun into yarn. Spinning for woolen yarns is typically done on a mule spinning machine, while worsted yarns can be spun on any number of spinning machines. After the yarn is spun, it is wrapped around bobbins, cones, or commercial drums.

After being carded, the wool fibers are spun into yarn. Spinning for woolen yarns is typically done on a mule spinning machine, while worsted yarns can be spun on any number of spinning machines. After the yarn is spun, it is wrapped around bobbins, cones, or commercial drums.

Carding

- 4 Next, the fibers are passed through a series of metal teeth that straighten and blend them into slivers. Carding also removes residual dirt and other matter left in the fibers. Carded wool intended for worsted yarn is put through gilling and combing, two procedures that remove short fibers and place the longer fibers parallel to each other. From there, the sleeker slivers are compacted and thinned through a process called drawing. Carded wool to be used for woolen yarn is sent directly for spinning.

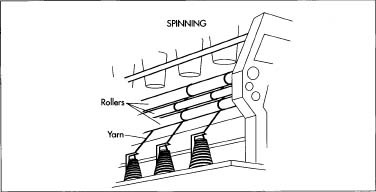

Spinning

- 5 Thread is formed by spinning the fibers together to form one strand of yarn; the strand is spun with two, three, or four other strands. Since the fibers cling and stick to one another, it is fairly easy to join, extend, and spin wool into yarn. Spinning for woolen yarns is typically done on a mule spinning machine, while worsted yarns can be spun on any number of spinning machines. After the yarn is spun, it is wrapped around bobbins, cones, or commercial drums.

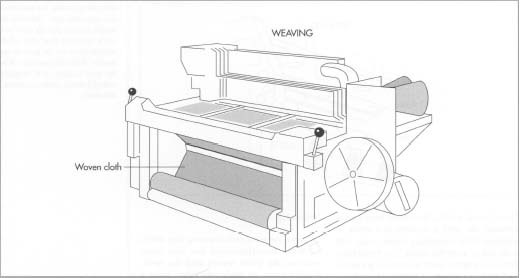

Weaving

-

6 Next, the wool yarn is woven into fabric. Wool manufacturers use two

basic weaves: the plain weave and the twill. Woolen yarns are made into

fabric using a plain weave (rarely a twill), which produces a fabric of

a somewhat looser weave and a soft surface (due to napping) with little

or no luster. The napping often conceals flaws in construction.

Worsted yarns can create fine fabrics with exquisite patterns using a twill weave. The result is a more tightly woven, smooth fabric. Better constructed, worsteds are more durable than woolens and therefore more costly.

Finishing

- 7 After weaving, both worsteds and woolens undergo a series of finishing procedures including: fulling (immersing the fabric in water to make the fibers interlock); crabbing (permanently setting the interlock); decating (shrink-proofing); and, occasionally, dyeing. Although wool fibers can be dyed before the carding process, dyeing can also be done after the wool has been woven into fabric.

Byproducts

The use of waste is very important to the wool industry. Attention to this aspect of the business has a direct impact on profits. These wastes are grouped into four classes:

Worsted yarns can create fine fabrics with exquisite patterns using a twill weave. The result is a more tightly woven, smooth fabric. Better constructed, worsteds are more durable than woolens and therefore more costly.

- Noils. These are the short fibers that are separated from the long wool in the combing process. Because of their excellent condition, they are equal in quality to virgin wool. They constitute one of the major sources of waste in the industry and are reused in high-quality products.

- Soft waste. This is also high-quality material that falls out during the spinning and carding stages of production. This material is usually reintroduced into the process from which it came.

- Hard waste. These wastes are generated by spinning, twisting, winding, and warping. This material requires much re-processing and is therefore considered to be of lesser value.

- Finishing waste. This category includes a wide variety of clippings, short ends, sample runs, and defects. Since this material is so varied, it requires a great deal of sorting and cleaning to retrieve that which is usable. Consequently, this material is the lowest grade of waste.

Quality Control

Most of the quality control in the production of wool fabrics is done by sight, feel, and measurement. Loose threads are removed with tweezer-like instruments called burling irons; knots are pushed to the back of the cloth; and other specks and minor flaws are taken care of before fabrics go through any of the finishing procedures.

In 1941, the United States Congress passed the Wool Products Labeling Act. The purpose of this act was to protect producers and consumers from the unrevealed presence of substitutes and mixtures in wool products. This law required that all products containing wool (with the exception of upholstery and floor coverings) must carry a label stating the content and percentages of the materials in the fabric.

This act also legally defined many terms that would standardized their use within the industry. Some of the key terms identified in the Act are:

- Wool. Refers to new wool. Can also include new fiber reclaimed from scraps and broken threads.

- Repossessed Wool. Material that is obtained from scraps and clips of new woven or felted fabrics made of previously unused wool.

- Reused Wool. Wool obtained from old clothing and rags that have been used or worn.

The Future

The current widespread use and demand for wool is so great that there is little doubt that wool will continue to maintain its position of importance in the fabric industry. Only a major innovation that encompasses the many attributes of wool—including it warmth, durability, and value—could threaten the prominence of this natural fiber.

Where To Learn More

Books

Botkin, M. P. Sheep and Wool: Science, Production, and Management. Prentice Hall, 1988.

Corbman, Bernard P. Textiles: Fiber to Fabric, 6th ed. McGraw-Hill, 1983.

Ensiminger, Eugene. Sheep and Wool Science. Interstate Printers, 1970.

Periodicals

Hyde, Nina. "Fabric of History: Wool," National Geographic. May, 1988, p. 552.

Ryder, Michael L. "The Evolution of the Fleece," Scientific American. January, 1987, p. 112.

— Dan Pepper

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: