Incense Stick

When the Three Wise Men brought their most precious gifts to Bethlehem, two of them—frankincense and myrrh were resins used to make incense. The third gift was gold, but it was the least valuable of these substances at that time. This relationship shows the importance that incense once held in our world. In modern times and in the Western world, the vast fragrance industry is dominated by perfumes, and incense manufacture and use is comparatively small. But, in fact, incense is the parent of perfumes. Incense is also the ancestor of many other products related to good smells. The importance of clean-smelling personal hygiene, bathrooms with sweetened air, laundry evoking the great outdoors, and romance-inspiring aromas originated with the powerful effects of incense in religious and public ceremonies.

Background

Incense comes from tree resins, as well as some flowers, seeds, roots, and barks that are aromatic. The ancient religions associated their gods with the natural environment, and fragrant plant materials were believed to drive away demons and encourage the gods to appear on earth; they also had the practical aspect of banishing disagreeable odors. Fashion is intensely linked to scents, and designers include signature scents to evoke the spirit of their clothes. That perfume originated from incense shows in the word itself; per and fumum mean through and smoke in Latin.

There are two broad types of incense. Western incense is still used in churches today and comes almost exclusively from the gum resins in tree bark. The sticky gum on the family Christmas tree is just such a resin, and its wonderful scent evokes the holidays. The gum protects the tree or shrub by sealing cuts in the bark and preventing infection. In dry climates, this resin hardens quickly. It can be easily harvested by cutting it from the tree with a knife. These pieces of resin, called grains, are easy to carry and release their fragrance when they are sprinkled on burning coal.

Eastern incense is processed from other plants. Sandalwood, patchouli, agarwood, and vetiver are harvested and ground using a large mortar and pestle. Water is added to make a paste, a little saltpeter (potassium nitrate) is mixed in to help the material burn uniformly, and the mix is processed in some form to be sold for burning. In India, this form is the agarbatti or incense stick, which consists of the incense mix spread on a stick of bamboo. The Chinese prefer the process of extruding the incense mix through a kind of sieve to form straight or curled strands, like small noodles, that can then be dried and burned. Extruded pieces left to dry as straight sticks of incense are called joss sticks. Incense paste is also shaped into characters from the Chinese alphabet or into maze-like shapes that are formed in molds and burn in patterns believed to bring good fortune. For all incense, burning releases the essential oils locked in the dried resin.

History

Incense has played an important role in many of the world's great religions. The Somali coast and the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula produced resin-bearing trees and shrubs including frankincense, myrrh, and the famous cedars of Lebanon. The cedar wood was transported all over the Tigris and Euphrates valleys, and the name Lebanon originated from a local word for incense.

The ancient Egyptians staged elaborate expeditions over upper Africa to import the resins for daily worship before the sun god Amon-Ra and for the rites that accompanied burials. The smoke from the incense was thought to lift dead souls toward heaven. The Egyptians also made cosmetics and perfumes of incense mixed with oils or unguents and blended spices and herbs.

The Babylonians employed incense during prayers and rituals to try to manifest the gods; their favorites were resins from cypress, fir, and pine trees. They also relied on incense during exorcisms and for healing. They brought incense into Israel before the Babylonian Exile (586-538 B.C. ), and incense became a part of ancient Jewish worship both before the Exile and after. True frankincense and myrrh from Arabia were widely used in the temples in Jerusalem during the times of Christ's teachings, although incense has fallen out of use in modern Jewish practice.

Both the ancient Greeks and Romans used incense to drive away demons and to gratify the gods. The early Greeks practiced many rites of sacrifice and eventually began substituting the burning of incense for live sacrifices. As a result of his conquests, Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C. ) brought back many Persian plants, and the use of incense in civic ceremonies became commonplace in Greek life. Woods and resins were replaced by imported incense as the Roman Empire expanded. The Romans encountered fine myrrh in Arabia, and the conquerors carried it as incense with them across Europe.

By the fourth century A.D. , the early Christians had incorporated incense burning into their practices, particularly the Eucharist when the ascending smoke was thought to carry prayers to heaven. Both the Western Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church used incense in services and processions, but incense has always been more intensely applied in the Eastern services. The rite of swinging the censer was and is used in many religions; the censer (also called a thurible in the West and a k dan in Japan) is suspended on chains and carried by hand. The Reformation ended the presence of in-cense in Protestant church practices, although its use returned to the Church of England after the Oxford Movement in the nineteenth century.

Incense was always employed more extensively in eastern religions. The Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist, and Shinto religions all burn incense in festivals, processions, and many daily rituals in which it is thought to honor ancestors. Incense burners, which are containers made of metal or pottery in which incense is burned directly or placed on hot coals, were first used in China as early as 2,000 B.C. and became an art form during China's Han dynasty (206 B.C. -220 A.D. ). These vessels had pierced lids to allow the smoke and scent to escape, and the designs from this period through the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) became increasingly omate with smoke-breathing dragons and other imaginative creations. The Chinese also applied incense to a wide variety of uses including perfuming clothes, fumigating books to destroy bookworms, and scenting inks and papers. Even the fan (an import into China from Japan) was constructed with sandal-wood forming the ribs so the motion of the fan would spread the fragrance of the wood.

In Japan, incense culture included special racks to hold kimonos so the smoke from burning incense could infiltrate the folds of these garments. Head rests were also steeped in incense fumes to indirectly perfume the hair. Clocks were made of incense sticks; different scents from the sticks told those tracking the time of the changing hours.

Raw Materials

Stick incense is made with "punk sticks" and fragrance oils. All the components are natural materials. The sticks themselves are imported from China and are made of bamboo. The upper portion of each stick is coated with paste made of sawdust from machilus wood, a kind of hardwood. The sawdust is highly absorbent and retains fragrance well. Charcoal is also used to make the absorbent punk, and it is favored in incense sticks made in India.

The fragrant oils are made of oil from naturally aromatic plants or from other perfumes or fragrances that are mixed in an oil base. Small quantities of paint are used to color-code

Design

The design of incense is based almost solely on fragrance. Incense makers carefully monitor trends in fragrances by obtaining samples from fragrance houses, discussing fashions and interests with their customers, and even noting those fragrances that are used in detergents, fabric softeners, and room air fresheners. When a fragrance seems like a possibility for use in incense, the manufacturer makes test batches of oils and incense sticks and gives employees and customers samples to burn at home. Positive feedback helps them select new incense fragrances.

The Manufacturing

Process

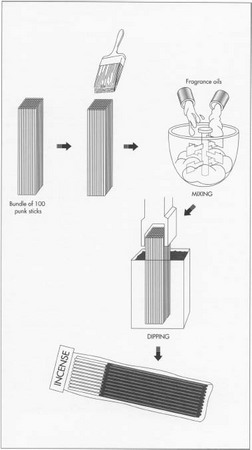

- At the incense factory, bundles of punk sticks arrive from a specialized supplier in China. Each bundle consists of 100 sticks. The ends of the sticks are cleaned by pounding the end of each bundle in front of a vacuum cleaner that sucks up the dust. The bundles are selected for a particular fragrance, and the even ends of the sticks, still tightly bundled, are painted with a color unique to that fragrance. The number of bundles designated for a particular fragrance is based on the popularity of the fragrance. For example, the factory may make 1,200 bundles (12,000 sticks of incense) with vanilla fragrance that is very popular; and it may make only 300 bundles (3,000 sticks of incense) in the green apple fragrance, which doesn't sell as well. After the ends are painted, the bundles are left overnight for the paint to dry.

- The next day, fragrance oils are mixed, and the punk-covered ends of the bundles are dipped in the fragrance. They are again left on shelves to dry overnight. A typical incense maker may stock hundreds of fragrances, some of which contain hundreds of elements to make their perfume. Many Indian scents are complex combinations of ingredients.

- The dried bundles are each wrapped in wax paper and sealed in 12 x 3 in (30.5 x 7.6 cm) ziplocking plastic bags. The bags are placed in bins. As orders are received for the incense sticks, they are individually packaged, packed in boxes made of recycled cardboard, and shipped for sale.

Byproducts/Waste

No byproducts are made, although incense manufacturers may make a wide range of fragrances in stick, cone, or powder form. Dust is the primary waste material and is contained by vacuuming and excellent ventilation. All paper goods are recyclable.

There are no safety hazards to employees, but there is a considerable risk to those with allergies. Potential employees are warned that the natural components of the sticks and the fragrances may cause allergic reactions, and some find they are unable to work in the factory because of this consideration.

The Future

Customs in incense manufacture have changed little over the centuries except in the range of fragrances offered. In ancient times, only naturally fragrant resins or woods like sandalwood and patchouli were used for incense. Modern fragrance production allows virtually any scent to be duplicated, and fragrances are available now that couldn't be offered before. Examples include green tea, candy cane, blueberry, pumpkin pie, and gingerbread incense.

The custom of use of incense is also likely to change in the future and in Western culture. In India, two or three sticks of incense may be burned every day in a typical home, while, in the United States, users of incense may only burn one stick a week. Incense-makers hope the variety, effectiveness, and low cost of incense sticks will make them more popular than air fresheners and room deodorizers made with artificial perfumes. Also, the popularity of meditation and aromatherapy have spurred incense sales among clients who want their rare moments of quiet and relaxation to be healing and beautifully scented.

Where to Learn More

Periodicals

Casson, Lionel. "Points of origin." Smithsonian (December 1986): 148+.

Karban, Roger. "Use of incense has unsavory past." National Catholic Reporter (December 8, 1995): 2.

Morris, Edwin T. Fragrance: The Story of Perfume from Cleopatra to Chanel. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1984.

Other

Wild Berry Incense, Inc. 1996. http://www.wild-berry.com/ (June 29, 1999).

— Gillian S. Holmes

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: