Violin Bow

Background

Several types of stringed musical instruments, among them the violin, the viola, and cello, cannot be successfully played without a bow, and are therefore referred to as "bowed stringed instruments." Because they are almost always heard while being bowed, the bow is considered an integral part of their tone production, contributing its own individual character and timbre. The use of different bows on the same instrument will produce correspondingly different tonality as a result. Most instrumentalists believe the bow's quality to be as important as the instrument's, and fine bows are therefore manufactured and selected with the utmost care.

History

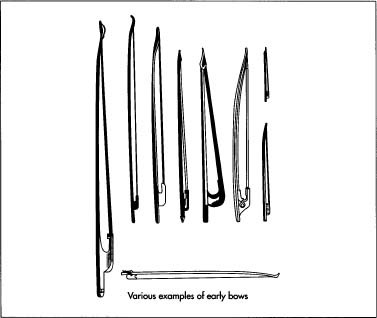

The practice of using a bow of some sort to make musical sound is so ancient that its origin can only be surmised. The most likely scenario is that the ancient hunting bow, its string treated with mixtures of wax and resin to hold the strands together, served as either instrument or bow in different contexts. From this primitive origin, the bow went through countless stages of evolution. The latest and most important to us today are the so-called "early" bow and the "modern" bow. All the bows of these types have important things in common: they are tapered sticks of special woods that are permanently bent to an arch, and have a flattened length of horsehair, stretched, under some tension, from end to end of the stick. One end is usually pointed, and the other squared off and usually fitted with a small raised portion to fasten and adjust the hair tension. The pointed end of each is called the "tip," and the raised portion of the other end, the "nut," or later, the "frog." (Experts are unclear as to how the latter name evolved.)

The early bow (sometimes referred to as the "baroque" bow) is based on the oldest and most obvious of designs, and has a curve that bows away from the hair. This type of bow was in common use until some time in the early 19th century, when the modern bow came into use. Although their design made these bows agile and responsive, their delicacy was not suitable for the pressure needed for louder and more forceful playing. As the concert halls and orchestras became larger, the violin family instruments received subtle modifications to suit the demands of the great performers. No modification was possible for the early bow however, and it suffered a swift extinction at the hand of the modern bow. After the modern bow's inception, the early bow became&Amost unheard of until it was revived in the late 1960s by early music enthusiasts seeking to recreate the ambiance of that time period.

The modern bow was a revelation after its introduction in France around the turn of the 19th century. The Tourte family is generally given credit for giving the modern bow its accepted final form, much as Antonio Stradivari contributed to the making of the violin. Modern bow manufacture reached its pinnacle in Paris between the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, and bowmakers came from all over Europe to collaborate with the famous French workshops and share their excellent reputation for bowmaking. The biggest changes in the modern bow involved inverting the curve of the stick into the hair, to give it more tension and resistance; shortening the tip to a squat hatchet-like

Raw Materials

The making of the bow begins with the selection and rough cutting of the correct woods and raw materials. Pemambuco wood is the accepted type of wood from which the stick of the bow is fashioned. Pernambuco wood grows only in the Amazon delta region in a Brazilian state of the same name. Actually there are several sub-species of this wood, many of which are completely extinct, and others which are rapidly nearing extinction. After harvesting, the logs are sawn into planks, and then into "blanks" which are cut into the rough outline resembling the stick and its tip. The ebony for the frog is split from log cross sections into small wedges which resemble the finished outside dimensions. Sheet silver or gold is prepared to the thickness of the various metal fittings, and a round ebony stick or dowel is prepared to make the adjuster barrel. The decorative pearl slide and pearl eyes are fashioned from specially milled sheets of abalone or mother of pearl shell, sawn and filed to rough size and shape.

The Manufacturing

Process

Roughing the stick

-

1 Roughing the stick refers to the process of carving and planing the

stick to its approximate finished dimensions. The squared off blank of

Pemnambuco wood is either held

across the corner of a bench, or along the length of a special board, and planed by hand with specially designed planes, fashioning the stick into its characteristic octagon shape. Using a direct heat device such as a spirit lamp or gas burner, the stick is heated slowly until it becomes flexible enough to bend. When ready, the stick is bent into an approximate or rough curve. When cooled, the stick is set aside, and the work on the frog begins.

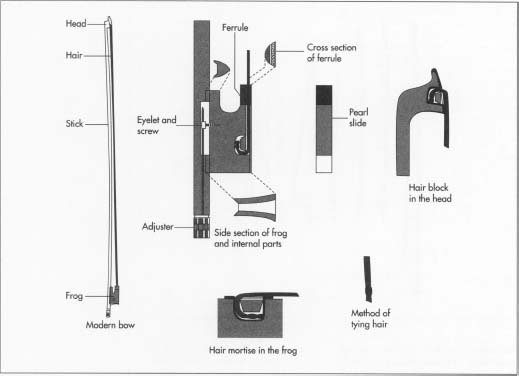

Major parts of a violin bow.

Major parts of a violin bow.

Roughing out the frog

-

2 The frog begins with the fashioning of the metal fittings. Several

parts require soldering as well as bending and shaping. The ferrule,

much like a half round ring, is a semicircular length of sheet silver

soldered to a flat one. The button for the adjuster needs one or two

silver rings. The other metal parts include a silver liner, which is

shaped to three facets of an octagon on a steel die, to conform to the

three facets on which it will contact the stick. If the frog is designed

with a back plate, the plate is shaped and bent to the 90 degree angle

of the back of the frog where it is to be inlaid.

The ebony wedge is trimmed to length and planed true to its center on all sides with a small razor sharp block plane. The various metal fittings are fit onto the frog in their respective places. Although modern commercial manufacture uses milling machinery to accomplish this part, the best modern builders have no problem doing this work by hand.

The fitting of the metal to the frog begins with drilling a 3-mm hole called the "throat" just under the area where the ferrule is located. The ferrule is fit onto the wider part of the throat with a knife and small chisels until it fits back flush and level. The sides are shaped concave with a gouge. The slot for the pearl slide, with its 20 degree under-cut sides, is next to be shaved out with the chisels. The cavity for the hair, called the hair mortise, is drilled and carved into the frog with a bow drill and chisel. The liner is then fit to the narrow edge of the frog's length using the chisels. The liner conformns to the top three facets of the stick's octagonal shape and is the bearing surface of the frog against the stick. A tapered silver back-plate extending from the back of the pearl slide slot to the center facet of the liner is inlaid to the flat end of the frog. The frog is then shaped using a knife, files, and small scrapers made of thin steel sheet. The decorations, called the eyes, are inlaid into the sides of the frog at this point. Then the ebony dowel for the adjuster button is fashioned separately on a lathe.

Fitting the frog to the stick

- 3 After the frog is done, the next job is to fit it to the roughed out stick. This is done by chalking the liner of the frog and rubbing it against the facets of the stick at the point where the frog makes contact. Through a process of marking the stick in this way and carefully planing, scraping, and filing the marks away, the frog is brought into the proper contact with the three bottom facets. Then holes are drilled in the stick for the screw and eye assembly which attaches the frog to the brass nut at the end of the stick.

Finishing the stick and frog

-

4 The first step here is to fit an ivory plate to the head or tip of the

bow. A plate of ivory is prepared with a raised section for the right

angle of the "beak" with a thin lamination of ebony veneer

all along its inside surface. The ivory is glued to the bottom face of

the head.

The shaping of the head is done with a knife and files. This work usually follows an established model and is accomplished with the means of a pattern or template, which is alternately traced and compared with the carving as it progresses. The elegant head models of the classic bows are often very beautiful, and have inspired connoisseurs the world over to collect them. All the great bowmakers imprinted their work with their own personal style, and experts are easily able to recognize most of the important styles, each head being akin to the signature of the maker. Once the head is finished, the mortise for the hair is cut into it, and the finishing of the stick can continue.

The stick must be now brought into final dimension, a process called graduation. The stick tapers from 3.5-5.0 mm just behind the head to 6.5-8.5 mm at the button end. Using a gauge or caliper, the craftsman skillfully planes this transition of thickness into the stick. The whole process must be done while preserving the integrity of a perfect octagon. The octagon's transition into the head is most difficult, and ends with the top three facets converging upwards, the two side facets becoming the side of the head, and the bottom three becoming the back of the head and the chamfers (a thin finish cut, at a 45 degree angle to the sides). All of this work is accomplished with either the plane in the case of the facets, or the knife and file for the detailing of the head. The stick is simply held by hand across a flat board or the corner of the workbench while planing the facets. The head is simply held in the hand while finishing.

If the stick is to be finished round, as many are, the edges of the octagon are planed away after graduation, and the stick is rounded off in this manner to an area about 1.6-2.4 inches (4-6 cm) in front of the frog. The area where one holds the bow is almost always octagonal.

Treating the stick

-

5 The bow usually has no real varnish as such because Pernambuco is

inherently dark and oily. But the stick may be subjected to a number of

chemical treatments to achieve its characteristic chocolate brown color.

Bathing the stick with nitric acid, and then following with a

neutralizing exposure to ammonia fumes is the most common color

treatment. The bow is given additional sheen and protection by a

technique known as "French polishing." This involves the

application of a dilute solution of shellac, sometimes mixed with other

gums or resins, with a lightly oiled rag held wrapped around the

fingers.

The roughing and finishing of bow sticks do not vary in technique from hand making to commercial manufacture. Most violin bows are made completely by hand. Only the speed of production, quality of materials, and diligence in finishing distinguish the difference between the mediocre and the sublime.

Lapping and hairing the bow

-

6 The lapping or winding acts as a grip for the stick and is often

called the "grip." It usually covers a 3-inch (7.6 cm)

length starting from just in front of the frog and going toward the tip.

It consists of some material, usually silver wire, wound in a compact

spiral fashion around the stick. Part of the winding nearest the frog is

covered with leather to protect the spot where the player's thumb

rests.

The hairing of the bow is quite routine, as the hair wears from playing and must be frequently replaced. The horsehair is purchased already selected, drawn, and bundled in uniform lengths. A small amount is separated from this and a small rosined knot is fashioned at one end using very strong thin thread. The knot is made stronger by inserting the end of the hair into the heat of a flame, and expanding the hair behind it. A small wooden plug is carved to fit the mortise in the head, and the hair is turned under and fastened into the head with this plug, which holds the hair spread across the top edge in a neat uniform flat strip. With the frog all the way forward, the hair is measured to length, cut off, and after much combing and arranging, tied in a similar way at the end near the frog. Another wooden plug is fashioned for the mortise of the frog. The ferrule is slid over the hair and after much more combing, the hair is turned over and fastened again with a wooden plug, this time into the frog. The hair is combed again before pushing in the pearl slide, and again after sliding on the ferrule. A wooden wedge is carved to fit the width of the ferrule so as to hold the hair spread in a ribbon-like fashion. After some more combing, the wedge is pushed into the ferrule against the hair and trimmed off with a knife. With the application of some rosin on the hair, for grip, the new bow is ready to play.

Where To Learn More

Books

Henderson, Frank. How to Make a Violin Bow. Murray Publishing Co., 1977.

Retford, William. Bows and Bow Makers. The Strad, 1964.

Roda, Joseph. Bows for Musical Instruments of the Violin Family. W. Lewis, 1959.

— Peter Psarianos

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: