Champagne

Background

Champagne is the ultimate celebratory drink. It is used to toast newlyweds, applaud achievements, and acknowledge milestones. A large part of its appeal is due to the bubbles that spill forth when the bottle is uncorked. These bubbles are caused by tiny drops of liquid disturbed by the escaping carbon dioxide or carbonic acid gas that is a natural by-product of the double fermentation process unique to champagne.

Today, fine champagne is considered a mark of sophistication. But this was not always so. Initially, wine connoisseurs were disdainful of the sparkling wine. Furthermore in 1688, Dom Perignon, the French monk whose name is synonymous with the best vintages, worked very hard to reduce the bubbles from the white wine he produced as Cellarer of the Benedictine Abbey of Haut-Villers in France's Champagne region. Ironically, his efforts were hampered by his preference for fermenting wine in bottles instead of casks, since bottling adds to the build-up of carbonic acid gas.

The Champagne province, which stretches from Flanders on the north to Burgundy in the south; from Lorraine in the east to Ile de France in the west, is one of the northern-most wine producing regions. For many years, the region competed with Burgundy to produce the best still red table wines. However, red grapes need an abundance of sun, something that the vineyards of Champagne do not receive on a regular basis. By the time Perignon took over the Abbey cellars in 1668, he was studying ways to perfect the harvesting of the Pinot Noir grape in order to produce a high-quality white wine.

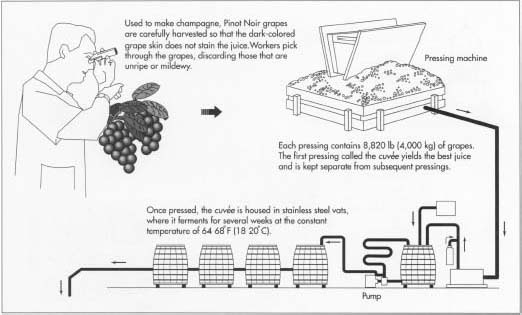

Often called black grapes, the Pinot Noir actually bears a skin that is blue on the outside and red on the inside. The juice is white but care must be taken during harvesting so that the skin does not break and color the juice.

Climate is a major factor in winemaking and nowhere is this more apparent that in the case of champagne. The inconsistency and shortness of the Champagne region's summers lead inevitably to inconsistent harvests. Therefore, a supply of wine made during better years is saved so that it may be blended with the juice of grapes harvested during poorer seasons. When the wine is stored after the fall harvest, it begins to ferment but ceases when the cold winter months set in. In late spring or early summer, the wine begins to ferment again. Extra sugar is added to that which is left in the wine. The wine is then bottled and tightly corked. The carbonic acid that would normally escape into the air if the wine were stored in casks builds up in the bottle, ready to rush forth when the cork is released.

In the early days of champagne-making, this volatility was something of a problem. Twenty to 90% of the bottles exploded, giving rise to the practice of wearing iron face masks when walking through champagne cellars. By 1735, a royal ordinance established regulations governing the shape, size, and weight of champagne bottles. Corks were to be 1.5 in (3.75 cm) long and secured to the collar of the bottle with strong pack thread. Deep cellars with constant temperatures also keep the bottles from exploding. The chalky earth of the Champagne region make it ideal for these cellars.

Three years after Perignon's death, Canon Godinot recorded the monk's specifications for the making of champagne:

- Use only Pinot Noir grapes.

- Prune the vine aggressively. Do not allow them to grow higher than three feet.

- Harvest the grapes carefully to keep the skins intact. Keep the grapes as cool as possible. Work the fields early in the morning or on showery days when the weather is very hot. Pick over the grapes while still in the fields. Reject all broken or bruised grapes.

- Set up the press as close to the fields as possible. If the grapes must be transported, use the slower pack animals such as mules or donkeys rather than horses to prevent the grapes from being jostled.

- Do not tread on the grapes or allow the skins into the juices.

Although modern champagne vintners have the use of technology to streamline certain parts of the champagne-making process, the steps have not changed significantly over the last three centuries.

Raw Materials

The main ingredient in champagne is the Pinot Noir grape. The grapes, left in bunches, are carefully picked so that the skin pigment does not stain the juice. Vineyard workers pick through the grapes, removing any that are unripe or mildewy. The grape bunches are weighed, generally 8,820 lb (4,000 kg) are used for a pressing. The grapes are taken directly to the press in a further effort to prevent the skin from coloring the juice.

During the double fermentation, several other natural ingredients are added to the wine. Yeast, usually saccharmonyces, is added during the first fermentation to help the grapes' natural sugar convert to alcohol. A liquer de tirage, cane sugar melted in still champagne wine, is added. In the second fermentation stage, a liquer d'expedition is added. This consists of cane sugar, still wine, and brandy. The amount of sugar added at this stage determines the type of champagne, from sweet to dry. Although each vintner has its own standards, the general guide is as follows: a 0.5% solution yields the driest champagne, known as brut;

The Manufacturing

Process

Pressing

- 1 The grapes are carefully loaded into the press, a square wooden floor surrounded by adjustable wooden rails and topped by a heavy oak lid. The lid is mechanically lowered and raised at intervals, causing the grapes to burst and the juice to pour out. The juices run through the rails into a sloped groove that carries the juice to stainless steel vats. The first pressing is called the cuvee and is the best juice from a batch of grapes. It is kept separate from subsequent pressings. The cuvee begins to ferment immediately. As scum rises to the top it is thrown off. Some of the scum falls to the bottom of the vat; this sediment is called lees. The juice, called must, continues to ferment for 24-36 hours when it gradually returns to its normal temperature.

First fermentation

- 2 The cuveés are moved into temperature-controlled stainless steels vats and fermented for several weeks at 64-68°F (18-20°C). The amount of time varies depending on the house specifications. Some champagne producers also put the wine through a malolactic fermentation process at this point to reduce acidity.

Blending the wines

- 3 The head cellarer (chefde caves) and cellar assistants taste and blend wines from several different pressings to obtain the desired taste. The blended wines are churned in vats by sweeping mechanical arms.

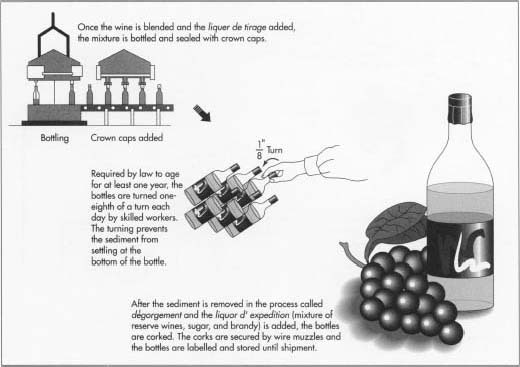

Bottling and the second fermentation

- 4 The blended wine is drawn off into bottles. The liquer de tirage is added and the bottles are sealed with crown caps. Because the carbonic acid cannot escape through the glass, it builds up to a tremendous pressure, equal to that in a bus tire.

Aging

- 5 French law requires that non-vintage wines be aged for at least one year. Vintage wines must be aged for at least three years. Each wine house adds to this minimum requirement as desired. Non-vintage wines are those that result from a thin harvest and are combined with reserves from past good vintages. Non-vintage wine is not sold under a particular year. Vintage wines, on the other hand, are made from Champagne grapes harvested in the same year. Vintage wines are rare, produced only when the summer has been unusually hot and sunny. The year is printed on the cork and the label.

Racking (Remuerurage)

- 6 During the aging period, the bottles of champagne are turned daily to keep the sediment caused by dead yeast cells from settling on the bottom. Skilled workers, with quick hands, twist the bottles one-eighth of a turn each day. The bottles start out in the horizontal position; by the end of the aging period, the bottles are vertical with the necks pointed towards the floor so that the sediment has collected on the inside face of the cork.

Dégorgement

- 7 The bottleneck is plunged into freezing liquid, causing a pellet of frozen champagne to form in the neck. The crown cap is carefully removed and the ice expels the sediment.

Liquor d'expedition is added

- 8 The mixture of reserve wines, sugar, and brandy is added to the bottles of champagne to create the desired sweetness.

Corkage

- 9 A long, fat cork that has been branded with the house name is hand-driven halfway into the bottleneck. Then the exposed portion is squashed down into the neck and secured with a wire muzzle. The bottles are labelled and stored in the cellar until shipment at which time they are packed into crates or cartons.

Quality Control

Guided by government regulations, each champagne house sets its own standards for the aging of its wines. In France, where the finest champagne is produced, the Institute National des Appelations d'Origin also places strict standards on the quality of soil that may be used for the growing of Champagne grapes. However, every champagne producing country regulates the production and marketing of its wines to some extent. Furthermore, each step of the champagne-making process is presided over by veteran experts who are skilled in tasting and blending.

The Future

It is inevitable that the labor-intensive process of making champagne will be further mechanized in the twenty-first century. Already, agricultural advances have reduced the threat of rot in the vineyard, thus reducing the number of workers needed to pick over the grapes in the fields. Some of the larger champagne houses have replaced the traditional round wooden press with a horizontal model inside of which a rubber bag inflates and gently presses the grapes against the sides of the press. Experiments are underway to develop a mechanized method for rotating the bottles to replace the costly hand-turning method. To date, none have proved effective, but industry observers believe that the change is in-escapable.

Where to Learn More

Books

Johnson, Hugh. Vintage: The Story of Wine. Simon and Schuster. 1989.

Simon, André. Wines of the World. 2nd ed. Ed. Serena Sutcliffe. McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Other

"How Champagne is Made." Moet & Chandon Homepage. http://moet.com/taste/made.html (January 21, 1997).

"Know-How." Jacquart Homepage. http:/Hwww.jacquart-champagne.fr/sf_eng.html (January 21, 1997).

— Mary F. McNulty

Some facts are incorrect, inaccurate or misspelled, i.e.,

Remuage is known as riddling, not racking. Racking is another process all-together.

Saccharomyces, Champagne (always capitalized).

And what is Carbonic acid? Perhaps you mean carbon dioxide? CO2?

Lees is not scum. Not even close.

Martha