Paper Currency

Background

The existence of money as a means of buying or selling goods and services dates back to at least 3000 B.C. , when the Sumerians began using metal coins in place of bartering with barley. The use of paper money began in China during the seventh century, but its uncertain value, as opposed to the more universally accepted value of gold or silver coins, led to widespread inflation and state bankruptcy. It was not until 1658, when Swedish financier Johann Palmstruck introduced a paper bank note for the Swedish State Bank, that paper money again entered circulation.

The first paper money in what is now the United States was issued by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1690. It was valued in British pounds. The first dollar bills were issued in Maryland in the 1760s. During the American Revolution, the fledgling Continental Congress issued Continental Currency to finance the war, but widespread counterfeiting by the British and general uncertainty as to the outcome of the revolution led to massive devaluation of the new paper money.

Stung by this failure, the United States government did not issue paper money again until the mid 1800s. In the interim, numerous banks, utilities, merchants, and even individuals issued their own bank notes and paper currency. By the outbreak of the Civil War there were as many as 1,600 different kinds of paper money in circulation in the United States—as much as a third of it counterfeit or otherwise worthless.

Realizing the need for a universal and stable currency, the United States Congress authorized the issue of paper money in 1861. In 1865, President Lincoln established the Secret Service, whose principal task was to track down and arrest counterfeiters. This early paper currency came in several different types, designs, and denominations, but had the common characteristic of being somewhat larger in size than today's money. It was not until 1929 that the current-sized bills went into circulation. In 1945, the government stopped printing bills in denominations greater than $100, and in 1963, they stopped printing silver certificate bills with the assurance that the dollar amount was available "…in silver payable to the bearer on demand."

Raw Materials

With paper money, the materials are as important as the manufacturing process in producing the final product. The paper, also known as the substrate, is a special blend of 75% cotton and 25% linen to give it the proper feel. It contains small segments of red and blue fibers scattered throughout for visual identification. Starting in 1990, the paper for $10 bills and higher denominations was made of two plies with a polymer security thread laminated between them. The thread was added to $5 bills in 1993. This thread is visible only when the bill is held up to a light and cannot be duplicated in photocopiers or printers.

The inks consist of dry color pigments blended with oils and extenders to produce especially thick printing inks. Black ink is used to print the front of the bills, and green ink is used on the backs (thus giving rise to the term greenbacks for paper money). The colored seals and serial numbers on the

Design

The design of the front and back of each denomination bill is hand tooled by engravers working from a drawing or photograph. Each engraver is responsible for a single portion of the design—one doing the portrait, another the numerals, and so on.

The portrait on the face of each bill varies by the denomination. George Washington appears on the $1 bill, Abraham Lincoln on the $5, up to Benjamin Franklin on the $100 bill. These persons were selected because of their importance in history and the fact that their images are generally well known to the public. By law, no portrait of a living person may appear on paper money.

In 1955, Congress passed a law requiring that the words "In God We Trust" appear on all U.S. currency and coins. The first bills with this inscription were printed in 1957, and it now appears on the back of all paper money.

Starting in 1990, very small printing, called microprinting, was added around the outside of the portrait. This printing, which measures only 0.006-0.007 inches (0.15-0.18 mm) high, repeats the words "The United States of America." It appears on all paper money except the $1 bill.

The Manufacturing

Process

In the United States, all paper money is engraved and printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which is part of the Department of the Treasury of the federal government. The Bureau also prints postage stamps, savings bonds, treasury notes, and many other items. The main production facility is located in Washington, D.C., and there is a smaller facility in Fort Worth, Texas. Every day, the Bureau prints approximately 38 million pieces of paper money. About 45% of this production are $1 bills and 25% are $20 bills. The rest of the production is divided between $5, $10, $50, and $100 bills. Although the $2 bill is still in circulation, it is rarely used, and therefore is rarely printed. Each bill, regardless of its denomination, costs the government about 3.8 cents to produce.

There are 65 separate operations in the production of paper money. Here are the major steps:

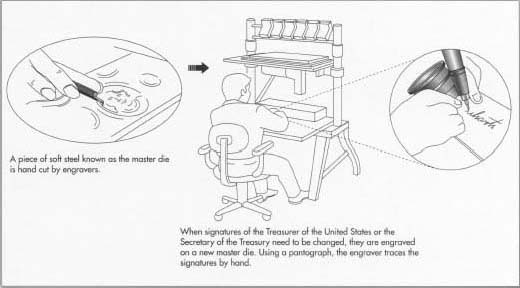

Engraving the master die

- 1 Engravers hand cut the design into a piece of soft steel, known as the master die, using very fine engraving tools and a magnifying glass. The portrait and images consist of numerous lines, dots, and dashes which are cut in various sizes and shapes. The fine crosshatched lines in the background of the portrait are produced by a ruling machine, and the scrollwork in the borders are cut using a geometric lathe.

- 2 Every time a new Treasurer of the United States or a new Secretary of the Treasury is appointed, their signatures must be engraved on a new master die for each denomination bill. First the signatures are photographically enlarged. An engraver then traces the signatures by hand with one end of a device known as a pantograph. This motion is mechanically reduced through a set of linkages, causing several diamond-tipped needles on the other end of the pantograph to cut the signatures into the master dies.

Making the master printing plate

- 3 Once the master die has been inspected, it is heated and a thin plastic sheet is pressed into it to form a raised impression of the design. Thirty-two of these raised plastic impressions are bonded together in a configuration of four across and eight down to form what is known as an alto. The master die is then placed in storage.

- 4 The plastic alto is placed in an electrolytic plating tank and is plated with copper. The plastic is stripped away leaving a thin plate of metal, known as a basso, with 32 recessed impressions of the design. The metal basso is then cleaned, polished, and inspected. If it passes inspection, it is plated with chromium to make the surface hard, and it becomes a master printing plate.

Printing the front and back of the bills

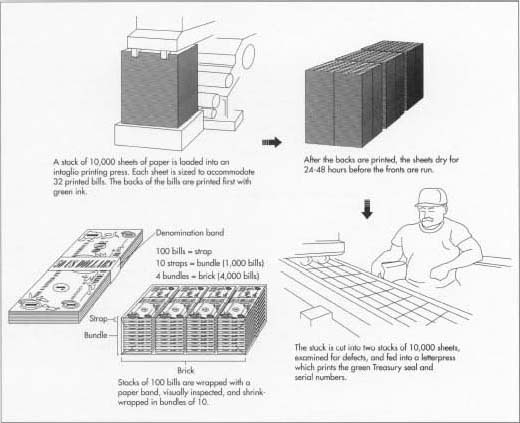

- 5 The principal printing process is known as intaglio printing. This process is used because of its ability to produce extremely fine detail that remains legible under repeated handling and is difficult to counterfeit. A stack of 10,000 sheets of paper is loaded into a high-speed, rotary intaglio printing press. Each sheet is sized to allow 32 individual bills to be printed on the same sheet. The paper is inspected to ensure that it contains the proper security thread for the denomination to be printed. A master printing plate of the proper denomination is secured around the master plate cylinder in the press.

- 6 The rotating master printing plate is coated with ink. A wiper removes the ink from the surface of the plate, leaving only the ink that is trapped in the engraved recesses of the design. A sheet of paper is fed into the press where it passes between the master plate cylinder and a hard, smooth impression cylinder under pressures reaching 15,000 psi (1,034 bar). The impression cylinder forces the paper into the fine, engraved lines of the printing plate to pick up the ink, leaving a raised image about 0.0008 in (0.02 mm) above the paper. This process is repeated at a rate of about 10,000 sheets per hour.

- 7 The printed sheets are then stacked on top of each other. The backs are printed with green ink first and are allowed to dry for 24-48 hours before the fronts are printed with black ink.

Printing the colored Treasury seal and serial numbers

-

8 After the intaglio printing process, the stacks are cut into two

stacks of 10,000 sheets and are visually examined for defects. Each

sheet is fed into a letterpress which prints the colored Treasury seal

and serial numbers on the face of the bills. Sixteen serial numbers are

printed at the same time. The press then automatically advances the

numbers before the next sheet of sixteen is printed. The numbers on any

sheet are separated by 20,000 between adjacent bills. Thus, the bill in

the upper left-hand corner of the first sheet would be serial number

0000001 and the one below it on the same sheet would be 0020001, and so

on. On the second sheet, all the numbers would advance by one giving

0000002 in the upper left, 0020002 below it, etc. In this manner, when

the sheets are cut into separate stacks, the bills within each stack

will have sequential serial numbers.

- 9 The finished sheets are inspected with machine sensors, and any printing errors, folded paper, inclusion of foreign objects, or other defects are identified. Any bills which are found to be defective are marked for later removal. Such bills are replaced with star notes which are numbered in a different sequence and have a star printed after the serial number.

Cutting and wrapping the bills

- 10 The sheets are gathered in stacks of 100 and cut into 16 individual stacks of 100 bills each with a vertical guillotine knife. Any bills which have been identified as defective are replaced with star notes at this time. The stacks of 100 bills are then wrapped with a paper band. The banded stacks are given a final visual inspection and are shrink-wrapped with plastic in bundles of 10 stacks. Four of these 10-stack bundles are then wrapped together to form a "brick" before they are shipped to the various federal reserve banks and other agencies.

Quality Control

Anything as important as money requires strict quality control standards. Flawed money is bad money and cannot be placed into circulation. In addition to the many inspections that occur during the printing process, the raw materials are also subject to strict inspections before they are used. The inks are tested for color, viscosity (thickness), and other properties. The paper is produced by a single manufacturer in a secret, tightly controlled process. The paper is tested for chemical composition, thickness, and other properties. It is illegal for anyone else to manufacture or possess this specific paper.

The finished bills are also tested periodically for durability. Some bills are put through a washing machine to determine the colorfastness of the inks, while others are repeatedly rolled into a cylinder and crushed on end to determine their resistance to handling. It is estimated that a bill can be folded and crumpled up to 4,000 times before it has to be replaced.

Destruction of Paper Money

Despite the use of high-quality paper and inks, the average life of a $1 bill in circulation is only about 18 months. Other denominations last somewhat longer. When a bill has been defaced, torn, or worn to the point where it is no longer identifiable or useable, it is taken out of circulation and returned to the federal reserve banks for destruction by shredding. Some of this shredded money is recycled to make roofing shingles or insulation. Money that is damaged or otherwise flawed during the printing process is shredded at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing plants.

The Future

For U.S. paper money, the future has arrived. Starting in 1996, the Department of the Treasury began issuing $100 bills with a new front and back design and several new security features designed to make counterfeiting more difficult. Other new bills in descending denominations will be printed at the rate of one new denomination per year.

The new bills use the same paper and are the same size and color as today's bills. Multicolor images, such as are commonly found on European currency, were not used because they were too easy to duplicate with color photocopies and printers. The image of Benjamin Franklin still appears on the front of the new $100 bill, although his portrait is larger and is shifted to the left. A watermark, formed by reducing the thickness of the paper during manufacture, has been placed to the right of the portrait and shows a second image of Franklin when the bill is held up to the light. The imbedded security thread is also still there, although now it has been treated to glow red under ultraviolet light. The position of the thread varies depending on the denomination of the bill to prevent the counterfeiting practice of bleaching the ink off lower denomination bills and reprinting them as higher denominations.

Other new features include concentric fine lines behind Franklin's head on the front and behind the image of Independence Hall on the back. These lines are so fine that they are extremely difficult for copiers or printers to duplicate without blurring them into a solid background. Microprinting, which was introduced in 1990, is used in two places on the new $100 bill; the words "USA 100" appear within the lower left-hand numeral 100, and the words "United States of America" run down the lapel of Franklin's coat.

Perhaps the most high-tech feature is a special color-shifting ink which is used to print the numeral in the lower right-hand corner. When viewed from head on, this ink appears green, but changes to black when viewed from the side.

Lower denomination bills will have many, but not all, of the security features present in the new $100 bills. The highest level of protection was given to the $100 bill because it is the largest denomination being printed. It is also the most common bill in circulation outside the United States, and hence, is frequently counterfeited in other countries.

Some of the security features originally proposed for the new money—such as holograms, plastic films, and coded fiber optics—were not used for this latest change because they represented too great a departure from the current money or because of potential technical problems.

Looking further into the future, paper money may eventually be replaced by electronic money that is downloaded onto plastic "stored value" cards from an ATM or computer. Each card would have a computer chip memory, and the money would be electronically transferred through a card reader to make purchases.

Where to Learn More

Books

Friedberg, Robert. Paper Money of the United States, 14th Edition. The Coin and Currency Institute, Inc., 1995.

Krause, Chester L. and Robert F. Lemke. Standard Catalog of U.S. Paper Money. Krause Publications, 1990.

Periodicals

Freeman, David. "Change For a Hundred." Popular Mechanics, January 1996, pp. 72-73.

Geschickter, J. "Making Money." National Geographic World, November 1996, pp.30-33.

Hirschkorn, Phil. "The Buck May Stop Here." George, April/May 1996, pp. 92+.

Lipkin, Richard. "New Greenbacks." Science News, January 27, 1996, pp. 58-60.

Schafrik, Robert E. and Sara E. Church. "Protecting the Greenback." Scientific American, July 1995, pp. 40-46.

Other

"Engravers." The Department of the Treasury. http://www.ustreas.gov/treasury/bureaus/bep/proc/new/engrav.html

"The Money Factory." The Department of the Treasury. http://www.ustreas.gov/treasury/bureaus/bep/proc/new/hq.html

"Your Money Matters." The Department of the Treasury. http://www.ustreas.gov/treasury/whatsnew/newcurr/home.html

— Chris Cavette