Charcoal Briquette

Background

Charcoal is a desirable fuel because it produces a hot, long-lasting, virtually smokeless fire. Combined with other materials and formed into uniform chunks called briquettes, it is popularly used for outdoor cooking in the United States. According to the barbecue Industry Association, Americans bought 883,748 tons of charcoal briquettes in 1997.

Basic charcoal is produced by burning a carbon-rich material such as wood in a low-oxygen atmosphere. This process drives off the moisture and volatile gases that were present in the original fuel. The resulting charred material not only burns longer and more steadily than whole wood, but it is much lighter (one-fifth to one-third of its original weight).

History

Charcoal has been manufactured since pre-historic times. Around 5,300 years ago, a hapless traveler perished in the Tyrolean Alps. Recently, when his body was recovered from a glacier, scientists found that he had been carrying a small box containing bits of charred wood wrapped in maple leaves. The man had no fire-starting tools such as flint with him, so it appears that he may have carried smoldering charcoal instead.

As much as 6,000 years ago, charcoal was the preferred fuel for smelting copper. After the invention of the blast furnace around 1400 A.D. , charcoal was used extensively throughout Europe for iron smelting. By the eighteenth century, forest depletion led to a preference for coke (a coal-based form of charcoal) as an alternative fuel.

Plentiful forests in the eastern United States made charcoal a popular fuel, particularly for blacksmithing. It was also used in the western United States through the late 1800s for extracting silver from ore, for railroad fueling, and for residential and commercial heating.

Charcoal's transition from a heating and industrial fuel to a recreational cooking material took place around 1920 when Henry Ford invented the charcoal briquette. Not only did Ford succeed in making profitable use of the sawdust and scrap wood generated in his automobile factory, but his sideline business also encouraged recreational use of cars for picnic outings. Barbecue grills and Ford Charcoal were sold at the company's automobile dealerships, some of which devoted half of their space to the cooking supplies business.

Historically, charcoal was produced by piling wood in a cone-shaped mound and covering it with dirt, turf, or ashes, leaving air intake holes around the bottom of the pile and a chimney port at the top. The wood was set afire and allowed to burn slowly; then the air holes were covered so the pile would cool slowly. In more modern times, the single-use charcoal pit was replaced by a stone, brick, or concrete kiln that would hold 25-75 cords of wood (1 cord = 4 ft x 4 ft x 8 ft). A large batch might burn for three to four weeks and take seven to 10 days to cool.

This method of charcoal production generates a significant amount of smoke. In fact, changes in the color of the smoke signal transitions to different stages of the process. Initially, its whitish hue indicates the presence of steam, as water vapors are driven out of the wood. As other wood components such as

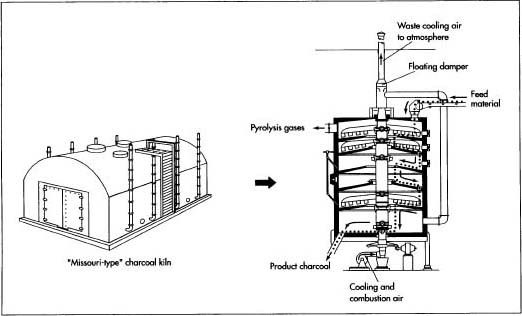

An alternative method of producing charcoal was developed in the early 1900s by Orin Stafford, who then helped Henry Ford establish his briquette business. Called the retort method, this involves passing wood through a series of hearths or ovens. It is a continuous process wherein wood constantly enters one end of a furnace and charred material leaves the other; in contrast, the traditional kiln process burns wood in discrete batches. Virtually no visible smoke is emitted from a retort, because the constant level of output can effectively be treated with emission control devices such as afterburners.

Raw Materials

Charcoal briquettes are made of two primary ingredients (comprising about 90% of the final product) and several minor ones. One of the primary ingredients, known as char, is basically the traditional charcoal, as described above. It is responsible for the briquette's ability to light easily and to produce the desired wood-smoke flavor. The most desirable raw material for this component is hardwoods such as beech, birch, hard maple, hickory, and oak. Some manufacturers also use softwoods like pine, or other organic materials like fruit pits and nut shells.

The other primary ingredient, used to produce a high-temperature, long-lasting fire, is coal. Various types of coal may be used, ranging from sub-bituminous lignite to anthracite.

Minor ingredients include a binding agent (typically starch made from corn, milo, or wheat), an accelerant (such as nitrate), and an ash-whitening agent (such as lime) to let the backyard barbecuer know when the briquettes are ready to cook over.

The Manufacturing

Process

The first step in the manufacturing process is to char the wood. Some manufacturers use the kiln (batch) method, while others use the retort (continuous) method.

Charring the wood

- 1 (Batch process) It takes a day or two to load a typical-size concrete kiln with about 50 cords of wood. When the fire is started, air intake ports and exhaust vents are fully open to draw in enough oxygen to produce a hot fire. During the week-long burning period, ports and vents are adjusted to maintain a temperature between about 840-950° F (450-510° C). At the end of the desired burning period, air intake ports are closed; exhaust vents are sealed an hour or two later, after smoking has stopped, to avoid pressure build-up within the kiln. Following a two-week cooling period, the kiln is emptied, and the carbonized wood(char) is pulverized.

-

2 (Continuous process) Wood is sized (broken into pieces of the proper

dimension) in a hammer mill. A particle size of about 0.1 in (3 mm) is

common, although the exact size depends on the type of wood being used

(e.g., bark, dry sawdust, wet wood). The wood then passes through a

large drum dryer that reduces its moisture content by about half (to

approximately 25%). Next, it is fed into the top of the multiple-hearth

furnace (retort).

Externally, the retort looks like a steel silo, 40-50 ft (12.2-15.2 m) tall and 20-30 ft (6.1-9.14 m) in diameter. Inside, it contains a stack of hearths(three to six, depending on the desired production capacity). The top chamber is the lowest-temperature hearth, on the order of 525° F (275° C), while the bottom chamber burns at about 1,200° F (650° C). External heat, from oil-or gas-fired burners, is needed only at the beginning and ending stages of the furnace; at the intermediate levels, the evolving wood gases burn and supply enough heat to maintain desired temperature levels.

Within each chamber, the wood is stirred by rabble arms extending out from a center shaft that runs vertically through the entire retort. This slow stirring process (1-2 rpm) ensures uniform combustion and moves the material through the retort. On alternate levels, the rabble arms push the burning wood either toward a hole around the central shaft or toward openings around the outer edge of the floor so the material can fall to the next lower level. As the smoldering char exits the final chamber, it is quenched with a cold-water spray. It may then be used immediately, or it may be stored in a silo until it is needed.

A typical retort can produce approximately 5,500 lb (2.5 metric tons) of char per hour.

Carbonizing the coal

- 3 Lower grades of coal may also be carbonized for use in charcoal. Crushed coal is first dried and then heated to about 1,100° F (590° C) to drive off the volatile components. After being air-cooled, it is stored until needed.

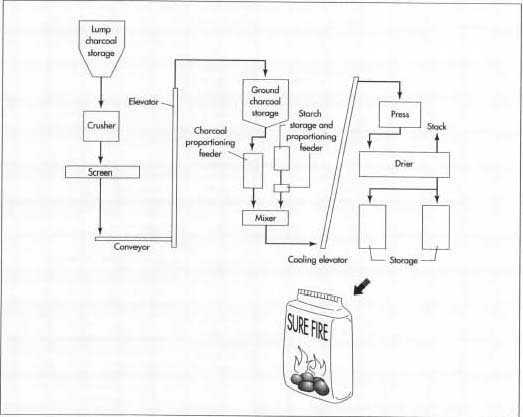

Briquetting

- 4 Charcoal, and minor ingredients such as the starch binder are fed in the proper proportions into a paddle mixer, where they are thoroughly blended. At this point, the material has about a 35% moisture content, giving it a consistency somewhat like damp topsoil.

- 5 The blended material is dropped into a press consisting of two opposing rollers containing briquette-sized indentations. Because of the moisture content, the binding agent, the temperature(about 105° F or 40° C), and the pressure from the rollers, the briquettes hold their shape as they drop out the bottom of the press.

- 6 The briquettes drop onto a conveyor, which carries them through a single-pass dryer that heats them to about 275° F (135° C) for three to four hours, reducing their moisture content to around 5%. Briquettes can be produced at a rate of 2,200-20,000 lb (1-9 metric tons) per hour. The briquettes are either bagged immediately or stored in silos to await the next scheduled packaging run.

Bagging

- 7 If "instant-light" briquettes are being produced, a hydrocarbon solvent is atomized and sprayed on the briquettes prior to bagging.

- 8 Charcoal briquettes are packaged in a variety of bag sizes, ranging from 4-24 lb. Some small, convenience packages are made so that the consumer can simply light fire to the entire bag without first removing the briquettes.

Byproducts/Waste

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, recovery of acetic acid and methanol as byproducts of the wood-charring process became so important that the charcoal itself essentially became the byproduct. After the development of more-efficient and less-costly techniques for synthesizing acetic acid and methanol, charcoal production declined significantly until it was revitalized by the development of briquettes for recreational cooking.

The batch process for charring wood produces significant amounts of particulateladen smoke. Fitting the exhaust vents with afterburners can reduce the emissions by as much as 85%, but because of the relatively high cost of the treatment, it is not commonly used.

Not only does the more constant level of operation of retorts make it easier to control their emissions with afterburners, but it allows for productive use of combustible off-gases. For example, these gases can be used to fuel wood dryers and briquette dryers, or to produce steam and electricity.

Charcoal briquette production is environmentally friendly in another way: the largest briquette manufacturer in the United States uses only waste products for its wood supply. Woodshavings, sawdust, and bark from pallet manufacturers, flooring manufacturers, and lumber mills are converted from piles of waste into useful briquettes.

The Future

Charcoal and briquette production methods have changed little in the past several decades. The most significant innovation in recent years has been the development of "instant-light" briquettes. A new version being introduced in 1998 will be ready to cook on in about 10 minutes.

Where to Learn More

Books

Emrich, Walter. Handbook of Charcoal Making: The Traditional and Industrial Methods. Hingham, MA: Kiuwer Academic Publishers, 1985.

Moscowitz, C. M. Source Assessment: Charcoal Manufacturing: State of the Art. Cincinnati, Ohio: Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Industrial Environmental Research Laboratory, 1978.

Periodicals

Scharabok, Ken. "Amaze Your Friends and Neighbors: Make Your Own Charcoal!" Countryside & Small Stock Journal (May 1997): 27-28.

Zeier, Charles D. "Historic Charcoal Production Near Eureka, Nevada: An Archaeological Perspective." Historical Archaeology 21(1987): 81-101.

— Loretta Hall

Chang CY