Hammer

Background

A hammer is a handheld tool used to strike another object. It consists of a handle to which is attached a heavy head, usually made of metal, with one or more striking surfaces. There are dozens of different types of hammers. The most common is a claw hammer, which is used to drive and pull nails. Other common types include the ball-peen hammer and the sledge hammer.

The concept of using a heavy object to strike another object predates written history. The use of simple tools by our human ancestors dates to about 2,400,000 B.C. when various shaped stones were used to strike wood, bone, or other stones to break them apart and shape them. Stones attached to sticks with strips of leather or animal sinew were being used as axes or hammers by about 30,000 B.C. during the middle of the Old Stone Age.

The dawn of the Bronze Age brought a shift from stone to metal in the toolmaker's art. By about 3,000 B.C. , axes with bronze or copper heads were being made in Mesopotamia, in what is now Iraq. The heads had a hole where a handle could be inserted and fastened. Nails made of copper or bronze were being used in the same area during the same period, suggesting that hammers with metal heads may have also existed. By about 200 B.C. , Roman craftsmen used several types of iron-headed hammers for wood working and stone cutting. A Roman claw hammer dating from about 75 A.D. had a striking surface on one side of the head, and a split, curved claw for pulling nails on the other side. It's appearance is so much like a modern claw hammer that you might expect to find it in a hardware store, rather than a museum.

With the development of commerce and the specialization of trades, many different hammer designs evolved. Coachbuilders, wheelwrights, blacksmiths, Pricklayers, stone masons, cabinetmakers, barrel makers (coopers), shoe makers (cobblers), ship builders, and many other craftsmen designed and used their own unique hammers. In 1840, a blacksmith in the United States named David Maydole introduced a claw hammer with the head tapering downwards around the opening for the handle. This provided additional bearing surface for the handle and prevented it from being wrenched loose when the hammer was used to pull nails. His hammer became so popular that his blacksmith shop grew into a factory to keep up with the demand. Most claw hammers made today use this same design.

Modern hammers come in a variety of shapes, materials, and weights. Although some specialty hammers are no longer used, there is still a wide array of hammer configurations as new designs are developed for new applications.

Types of Hammers

In general, hammers have metal heads and are used to strike metal objects. The curved claw hammer used to drive nails into wood is one example. Other hammers include the framing hammer with a straight claw that can be driven between nailed boards to pry them apart. It is often used in heavy construction where temporary forms or supports must be removed. The ball peen hammer has a semi-spherical end and is used to shape metal. A tack hammer is one of the smallest hammers. It is used by upholsterers to drive small tacks into wood furniture frames. A sledge hammer is one of the largest hammers. It usually has a long handle and is used for driving spikes and other heavy work. Other modern hammers include brick hammers, riveting hammers, welder's hammers, hand drilling hammers, engineer's hammers, and many others.

A related class of hammer-like tools are called mallets. They have large heads made of rubber, plastic, wood, or leather. Mallets are used to strike objects that would be damaged by a blow from a metal hammer. Rubber mallets are used to assemble furniture or to beat dents out of metal. Wood and leather mallets are used to strike wood handled chisels. Plastic mallets have smaller heads and are used to drive small pins into machinery. A very large wooden mallet is sometimes called a maul.

Design

The two major components of a hammer are the head and the handle. The design of these two components depends on the specific application, but all hammers have many common features.

The striking surface of the head is called the face. It may be flat, called plain faced, or slightly convex, called bell faced. A bell-faced hammer is less likely to bend a nail if the nail is struck at an angle. Another face design is called a checkered face. It has crosshatched grooves cut into the surface to prevent the hammer from glancing off the nail head. Because it leaves a checkered impression on the wood, it is usually only found on framing hammers used for rough construction.

The surface of the head around the face is called the poll. The poll is connected to the main portion of the head by the slightly tapered neck. The hole where the handle fits into the head is called the adze (adz) eye. The side of the head next to the adze eye is called the cheek.

On the opposite end of the head, there may be a claw, a pick, a semi-spherical ball peen, or a tapered cross peen depending on the type of hammer. There may also be a second face, as in a double-faced sledge hammer.

Hammers are classified by the weight of the head and the length of the handle. The common curved claw hammer has a 7-20 oz (0.2-0.6 kg) head and a 12-13 in (30.5-33.0 cm) handle. A framing hammer, which normally drives much larger nails, has a 16-28 oz (0.5-0.8 kg) head and a 12-18 in (30.5-45.5 cm) handle.

Raw Materials

Hammer heads are made of high carbon, heat-treated steel for strength and durability. The heat treatment helps prevent chipping or cracking caused by repeated blows against other metal objects. Certain specialty hammers may have heads made of copper, brass, babbet metal, and other materials. Dead-blow hammers have a hollow head filled with small steel shot to give maximum impact with little or no rebound.

The handles may be made from wood, steel, or a composite material. Wood handles are usually made of straight-grained ash or hickory. These two woods have good cross-sectional strength, excellent durability, and a certain degree of resilience to absorb the shock of repeated blows. Steel handles are stronger and stiffer than wood, but they also transmit more shock to the user and are subject to rust. Composite handles may be made from fiberglass or graphite fiber-reinforced epoxy. These handles offer a blend of stiffness, light weight, and durability.

Steel and composite handles usually have a contoured grip made of a synthetic rubber or other elastomer. Wood handles do not have a separate grip. Steel and composite handles may also be encased in a high-impact polycarbonate resin. The addition of this material around the handle increases shock absorption, improves chemical resistance, and offers protection against accidental overstrikes. An overstrike is when the hammer head misses the nail and the handle takes the impact instead. This is a common cause of handle failure.

There are several materials and methods used to attach the head to the handle. Wood handle hammers use a single thin wood wedge driven diagonally into the upper end

The Manufacturing

Process

The manufacturing process varies from one company to another depending on the company's production capacity and proprietary methods. Some companies make their own handles, while others purchase the handles from outside suppliers.

Here is a typical sequence of operations for making a claw hammer.

Forming the head

- 1 The head is made by a process called hot forging. A length of steel bar is heated to about 2,200-2,350° F (1,200-1,300° C). This may be done with open flame torches or by passing the bar through a high-power electrical induction coil.

- 2 The hot bar may then be cut into shorter lengths, called blanks, or it may be fed continuously into a hot forge. The bar or blanks are positioned between two formed cavities, called dies, within the forge. One die is held in a fixed position, and the other is attached to a movable ram. The ram forces the two dies together under great pressure, squeezing the hot steel into the shape of the two cavities. This process is repeated several times using different shaped dies to gradually form the hammer head. The forging process aligns the internal grain structure of the steel and provides much stronger and more durable piece.

- 3 During this process, some of the hot steel squeezes out around the edges of the die cavities to form flash, which must be removed. As a final step the head is placed between two trimming dies, which are forced together to cut off any protruding flash. The head is then cooled, and any rough spots are ground smooth.

-

4 In order to prevent chipping and cracking of the hammer head in

service, the face, poll, and claws are heat treated to harden them. This

is done by heating those

areas, either with a flame or an induction coil, and then quickly cooling them. This causes the steel near the surface to form a different grain structure that is much harder than the rest of the head.

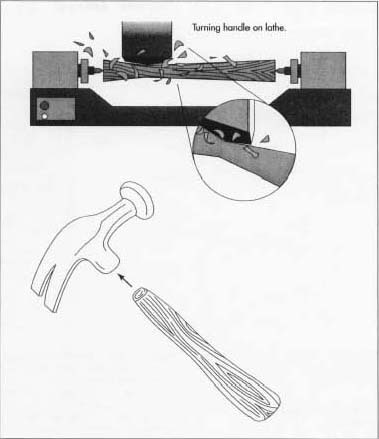

In order to make a wooden handle, the wood is cut to the desired length and then shaped into a handle on a lathe.

In order to make a wooden handle, the wood is cut to the desired length and then shaped into a handle on a lathe. - 5 The heads are cleaned with a stream of air containing small steel particles. this process is called shot blasting. The head may then be painted.

- 6 The face, poll, claws, and cheeks are polished smooth. This removes the paint in those areas. As part of this operation, the v-shaped slot in the claws is smoothed using an abrasive disc.

Forming the handle

- 7 If the hammer has a wood handle, it is formed on a lathe. A piece of wood is cut to the desired length and secured at each end in the lathe. As the wood spins around the long axis of the handle, a cutting tool moves in and out rapidly to cut the handle profile. The position of the cutting tool is driven by a cam that has the same shape as the finished handle. As the cutting tool moves down the length of the handle, it follows the shape of the cam and cuts the handle to match it. The finished handle is clamped in a holding device and a slot is cut diagonally across the top of the handle. The handle is then sanded to give it a smooth surface.

- 8 If the hammer has a steel-core handle, the core is formed by heating a bar of steel, until it becomes plastic, and forcing it through an opening that has the desired cross-sectional shape. This process is called extrusion. If the hammer has a graphite fiber-reinforced core, the core is formed by gathering together a bundle of graphite fibers and pulling them through an opening that has the desired cross-sectional shape while epoxy resin is forced through the opening at the same time. This process is called pultrusion. In either case, the core may then have a protective plastic jacket molded around it.

Assembling the hammer

- 9 If the hammer has a wood handle, the handle is inserted up through the adze eye of the head. A wood wedge is tapped down into the diagonal slot on the top of the handle to force the two halves outward to press against the head. This provides sufficient friction to hold the head on the handle. The wood wedge is secured in place with two smaller steel wedges driven through it crossways. The handle may then be stenciled with ink or labeled with an adhesive sticker to show the manufacturer, brand name, or other information.

- 10 If the hammer has a steel or graphite fiber-reinforced core, the handle is inserted up through the adze eye of the head. Liquid epoxy resin is then poured through the top of the hole to bond the handle in place. The handle is placed in a hollow die and a rubber grip is molded around its lower portion. The handle may then be labeled with an adhesive sticker to show the manufacturer, brand name, or other information.

Quality Control

In addition to the normal visual inspections and dimensional measurements, various steps in the manufacturing process are monitored. Probably the most important step is the heat treatment used to harden portions of the head. The temperatures and rate of heating and cooling are critical in forming the proper hardness, and the entire operation is closely controlled.

The Future

Having survived for thousands of years, it is unlikely that the hammer will disappear from civilization's toolbox anytime soon. It does have some serious competition though. The most formidable competitor is the gas-driven nail gun. This device uses a compressed gas, usually air, to drive a nail into wood with a single shot. Although nail guns are heavier and more expensive than hammers, they are also significantly faster. This is especially true in repetitive nailing operations such as installing floor or roof sheathing for new home construction. Nail guns are also favored in areas where noise is a concern. Because a nail gun can drive a nail in a single shot, it produces much less over-all noise than the five or six hammer blows it takes to drive a nail.

Where to Learn More

Books

Salaman, R.A. Dictionary of Tools. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1975.

Vila, Bob. This Old House Guide to Building and Remodeling Materials. Warner Books, Inc., 1986.

Periodicals

Capotosto, Rosario. "Hammer Basics." Popular Mechanics (October 1996): 104-107.

Neary, John. "When rules and drills drive you just plane screwy." Smithsonian (February 1991): 52-60, 62-65.

Other

Stanley Tools. http://www.stanleytools.com .

— Chris Cavette