Baseball Glove

Background

Wearing a glove to protect one's catching hand was not considered a manly thing to do in the years following the Civil War, when the game of baseball spread through the country with the speed of a cavalry charge. It's uncertain who was the first to wear a baseball glove; nominees include Charles G. Waite (or Waitt), who played first base for a professional Boston team in 1875, and Doug Allison, a catcher for the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1869. Waite was undoubtedly concerned about his reputation; the gloves were flesh colored to make them less obvious.

By 1880, a padded catcher's mitt had appeared, and by the turn of the twentieth century, most players were wearing gloves of one sort or another. By today's standards of workmanship, and by current expectations of what a glove can do for a fielder, the gloves of that time were primitive.

Although the early gloves were not impressive by today's standards, they still required a high level of craftsmanship to produce. Gloves were and are a labor-intensive product calling for a large amount of individual attention. Most of them were heavily padded affairs that covered and protected the catching hand by virtue of the glove's thickness, but did little else. It wasn't until the late 1930s that the design of the glove as an aid to both catching and playing became a matter of importance. Even baseball gloves of twenty years ago seem antique compared to present-day relatives in their ability to protect the hand and help a player catch a ball.

A modern player can now, with his modern glove, make one handed catches; behind the plate, a catcher uses his flexible, fitted mitt with the surgical sureness of a doctor, plucking a ball from the air as if he were using a pair of tweezers to remove a splinter. The two-handed catch, a fielding skill required up to only a few years ago and necessary when gloves were just large pads, now is considered a useful but hardly necessary talent.

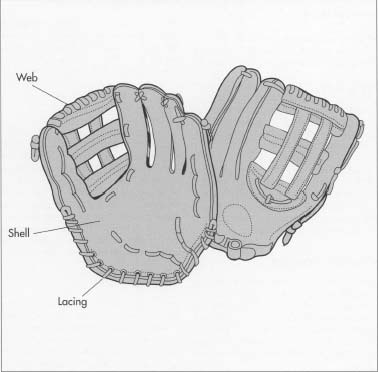

Differences among today's gloves vary from the thickness of the heel to the design of the web to the deepness of the palm. Outfielders tend to prefer large gloves with deep palms, to make catching fly balls easier. Infielders generally like smaller gloves into which they can reach easily to grip and throw the ball to another player. Most outfielders will break a glove in vertically; infielders tend to prefer gloves broken in horizontally.

Improvements in the design of the glove and the efficiency and protection it offers a ball player are ongoing. It looks like quite a simple thing, yet a baseball glove is the fruit of more than one hundred years of history and more than thirty patents. A baseball glove is reflective of a very special creative design process that is still very much alive.

Raw Materials

Except for small plastic reinforcements at the base of the small finger and the thumb, and some nylon thread, a glove is made totally of leather, usually from cattle. The Texas-based Nocona Glove Company, however, uses a large quantity of kangaroo hide from Australia in addition to leather from cattle. Kangaroo hide is somewhat softer than leather, and the glove can be used after a shorter breaking-in period than usual.

Generally, cowhides are the predominant material in use today, as in the past. Beef cattle hides (two to a steer) are processed by a tannery, and the finest hides, those without brands, nicks, or other blemishes are sent to the glove factories. Tanning is a chemical treatment of the hides to give them required characteristics, such as flexibility and durability. If leather were not tanned, it would dry and flake in extremely short order. Some glove companies compete for quality hides with makers of other fine leather products. The Rawlings Company depends on one tannery and buys all of the tannery's product.

Each cowhide provides the leather for three or four gloves. Rawlings, however, cuts and tans its own leather for lacing, which has different requirements for durability and flexibility than the rest of the glove. Various synthetic materials have been tested for baseball gloves, but so far none have demonstrated the resilience, the stretchability, and the feel that leather has, and no replacement for leather is on the immediate horizon.

The Manufacturing

Process

By the time cowhides arrive at the factory, they have already been cured (salting or drying to kill bacteria) and tanned (chemically treated to prevent putrefaction), all of which prepares them to be turned into gloves. Once at the factory, the cowhides are graded for such things as color and tested in a laboratory for strength.

The manufacturing process for baseball gloves is fairly simple: the various parts of the glove are cut and then sewn together with a long string of rawhide leather. Below is a more detailed explanation:

Die-cutting the glove parts

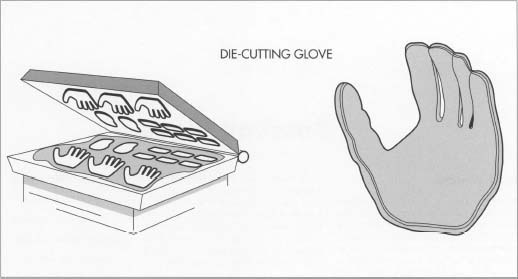

- 1 The parts of the hide that will be used for gloves are die-cut (i.e. cut automatically with a machine that simulates a cookie cutter) into four parts—the shell, lining, pad, and web.

- 2 Early in the process, sometimes even before the leather is cut, the lettering—usually foil tape—identifying the manufacturer is burned into the leather with a brass stamping die.

Shell and lining

-

3 The shell of the glove is sewn together while inside-out. It is then

turned right-side-out, and its lining is inserted. Before being

reversed, the shell is mulled (wetted or

steamed for flexibility) so that it doesn't crack or rip when it is turned.

The lacing around the edges of a glove is usually one piece of rawhide that might be as much as 80 to 90 inches in length. The lacing begins at the thumb or lithe finger and holds the entire glove together. Like nearly every other step in baseball glove manufacture, the lacing must be done manually.

The lacing around the edges of a glove is usually one piece of rawhide that might be as much as 80 to 90 inches in length. The lacing begins at the thumb or lithe finger and holds the entire glove together. Like nearly every other step in baseball glove manufacture, the lacing must be done manually. - 4 The turned shell is put on a device known as a hot hand, which is a hand-shaped metallic form; its heat helps the shell form to its correct size. At this point, the hot hand also assures that all the openings for the fingers (finger stalls) are open correctly.

Inserting the pad and plastic

reinforcements

- 5 A pad is inserted into the heel of a glove. Better gloves have two-part pads that make it easier for the glove to flex in the correct direction when squeezed. The padding in a glove is made of two layers of leather, hand stitched together. Catchers' mitts, which need a thicker palm than other gloves, are made with five layers of leather padding.

- 6 At this same point, plastic reinforcements are inserted at the thumb and toe (little finger) sections of the glove. These devices provide added support for the glove and protect the player's fingers from being bent backwards accidentally.

Web

- 7 Before all the parts of the glove are laced together, the web is fabricated out of several pieces of leather. The web can consist of anywhere from two to six pieces of leather, depending on the type of web desired.

Lacing and stitching

- 8 The lacing around the edges of a glove is usually one piece of rawhide that might be as much as 80-90 inches (203-228 centimeters) long. The lacing begins at the thumb or little finger and holds the entire glove together. The final lacing operation is at the web section. Some non-leather stitching is needed for the individual parts—the web, for instance, is usually stitched together with nylon thread.

- 9 The strap across the back of the hand of a glove used to be lined with shearling (sheepskin); a synthetic material is now used.

- 10 Catchers' mitts and first base gloves 1 O are hand assembled and sewn from four parts—palm, pad, back, and web. The palm and back are sewn together first, and then joined together with the other pieces with rawhide lacing.

- 11 The final step is called a lay off operation; the glove is again placed on a hot hand to adjust any shaping problems and to make sure that the openings for the fingers (finger stalls) have remained open throughout the manufacturing process.

Quality Control

Quality control starts when the hides arrive at the factory, where they are graded for such things as color and tested in a laboratory for strength. Even after a hide is accepted by a manufacturer, only a part of it will be usable; Rawlings uses about 30 percent of a hide, from which it is able to make three or four gloves.

Because making a glove requires so much personal attention at each step, there is little need for a manufacturer to maintain a full-blown, quality control department. Each craftsman involved in the process functions as his or her own quality control person, and if a defect in a glove becomes apparent, the person who is working on the glove is expected to see that the glove is removed from production.

As happens in many areas where a product has undergone almost continuous design changes for years and years, there are those who believe that the older methods and products are better than the new ones. The Gloveman (Fremont, California), operated by Lee Chilton, specializes in restoring old gloves for current use (although it has its own line of catcher's mitts), and Chilton is quite serious in his assertion that one of the best ways to get a good glove is to buy an old one at a flea market, tag sale or second hand store, and let his company restore it.

Professional Gloves

Although professional gloves might be examined with a more critical eye before use, and might be the choicest specimens, they are the same gloves, sans autographs, that anyone can buy in a store. In exchange for autograph endorsements, professionals receive free gloves (and a fee) from manufacturers.

It is unusual for a professional ball player to experiment with different models of gloves, or to request an unusual design. According to Bob Clevenhagen, Master Glove Designer at Rawlings, ball players tend to be "conservatives who stick with what works." By the time a ballplayer is a professional, he has found the right glove for himself, and keeps using it. Most professionals are using the same or similar model glove that they used in college, high school, or even little league.

The Future

As is true of many older products where refinement is the primary goal of the manufacturers, baseball glove design is not changing as rapidly as it did in the past. Previous developments included such things as holding the fingers of the glove together with lacing, changes in the design of the pocket and the heel of the glove, and redesigning the catcher's glove so that a catcher can handle a ball with one hand, like other fielders. In the 1950s, Rawlings even devised a six-fingered glove at the request of Stan Musial, who wanted a single glove that could be used both at first base and at other infield positions.

Large glove manufacturers have seen different designs go in and out of style, and some of their most famous models have been retired from production (such as the Rawlings Playmaker, a popular glove of the 1950s).

Current changes have focused on how the glove is used in relation to other players. Catchers' mitts, for example, now have a bright, fluorescent edging to make a better target for a pitcher. In August, 1992, The Neumann Tackified Glove Company (Hoboken, New Jersey) announced that it would begin making black gloves with a white palm so that the glove will be a better target for one player throwing a ball to another.

Where To Learn More

Books

Thorn, John and Bob Carroll, eds. The Whole Baseball Catalogue. Fireside, 1990.

Periodicals

Feldman, Jay. "Working Hand In Glove," Sports Illustrated. April 6, 1987, pp. 146-150.

Javor, Ted. "His Innovation Really Caught On," Sporting News. June 25, 1990, p. 6.

Lindburgh, Richard. "It's a Brand New Ballgame: Sports Equipment for the 1990s," USA Today. May 2, 1990, p. 90-92.

Lloyd, Barbara. "A Baseball Glove Made To Help With Throwing," New York Times. August 22, 1992, p. 46a.

Wulf, Steve and Jim Kaplan. "Glove Story," Sports Illustrated. May 7, 1990, pp. 66-82.

— Lawrence H. Berlow